Our community project work

Legacies of Slavery: Reflecting on a Complex Heritage in Rural Scotland

The small village of Aberlour, which is beautifully situated near the river Spey in Moray and is famed for a whisky of the same name, and the even smaller neigbouring village of Craigellachie, stand as testaments to resilience, faith, and community spirit. Yet, like many places across Scotland, their history is entangled with the darker legacies of the transatlantic slave economy. A new project, Legacies of Slavery: Churches, Communities and Buiding a Fairer Future, led by Dr Jim MacPherson of the University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI) in partnership with the Church of Scotland, invites the local community to engage thoughtfully with this complex past.

Using the case study of Alexander Grant of Aberlour and his niece, Margaret MacPherson Grant, the project encourages reflection on how the money made from chattel slavery in Jamaica were channelled back into the local community—particularly through the endowments that funded the building of Aberlour’s local Episcopal church. Through research, education, and creative expression, this initiative aims to foster an honest dialogue about the ways historical injustices continue to shape the present.

A Legacy Rooted in Jamaica

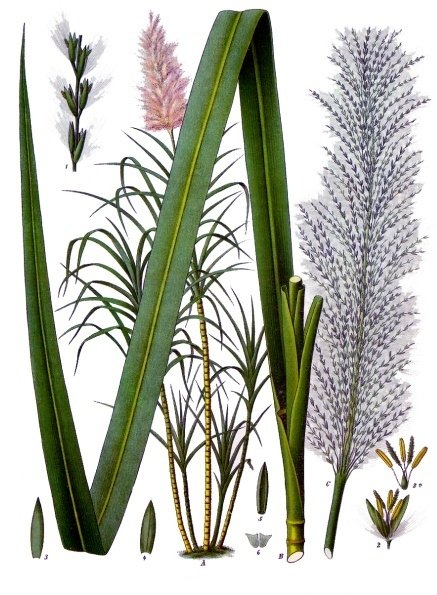

Alexander Grant’s life epitomises the intersections between Scotland’s local histories and the global reach of the British Empire. As an enslaver operating in Jamaica during the height of the transatlantic slave trade, Grant amassed considerable wealth from the forced labour of enslaved Africans producing sugar and rum. This wealth did not remain distant. Upon returning to Scotland, the money was infused into his local community through investments, philanthropy, and, notably, then through his niece, Margaret MacPherson Grant.

Margaret, who inherited a significant portion of Alexander Grant’s fortune, became a well-known benefactor in Aberlour. Among her most enduring contributions was her financial support for the construction of the local Episcopal parish church—a structure still central to village life today. Yet beneath its stone walls and stained glass lies a more troubling story: one that ties the fabric of a Scottish community to the brutal realities of Caribbean plantations.

Uncovering and Confronting Hidden Histories

The Legacies of Slavery project seeks not to erase or diminish the importance of the church and its place in the community, but rather to provide a fuller, more honest understanding of how it came to be. By focusing on Alexander and Margaret’s intertwined stories, the project opens a necessary space for local people to consider how slavery’s profits helped shape their familiar surroundings.

This approach reflects a broader movement across Scotland and the wider UK to reckon with the deep imprints of slavery on national and local histories. Through research and public engagement, communities like Aberlour and Craigellachie are beginning to ask difficult but essential questions: Whose suffering financed our heritage? How should we commemorate benefactors whose wealth was built on human misery? How do we balance pride in local traditions with an awareness of their origins?

The Colonial Countryside project, led by Professor Corinne Fowler of the University of Leicester in collaboration with the National Trust, exemplified how difficult histories—particularly those involving chattel slavery and colonialism—can be meaningfully explored through creative expression. This pioneering initiative engaged around 100 children from diverse backgrounds in researching and reinterpreting the colonial histories of (English) National Trust properties. Through writing workshops, public speaking events, and the co-creation of exhibitions, these young participants brought to light the often-overlooked connections between Britain’s country houses and its imperial past. Their creative outputs not only enriched public understanding but also demonstrated that confronting uncomfortable aspects of history can foster education, empathy, and dialogue within communities.

This video below is my favourite outcome of this project, which I am sure you will agree is beautiful.

Creativity & Healing Through Textiles

One of the project’s most innovative components involves the use of creative textile art to engage with these heavy themes. Jo Watson of Làmhan, a former UHI postgraduate student who studied the legacies of slavery under Dr MacPherson, will be leading a series of textile workshops for children and parishioners. These sessions aim to explore sensitive histories through tactile, participatory means. Jo will be leading sessions with local communities and schools in May and June 2025.

Textile work has long been a medium for storytelling and memory-keeping. By designing then stitching, and creating together, participants are offered a gentle but profound way to process difficult knowledge and to contribute to a new, collective memory for Aberlour and Craigellachie —one that acknowledges pain but also looks toward hope and understanding.

Jamaican bandana cloth, characterised by its vibrant check patterns, has a complex history that intertwines colonial legacies with cultural reclamation. Originally produced in Madras (now Chennai), India, this lightweight cotton fabric was exported by the British during the late 18th - 19th century to clothe enslaved individuals in the Caribbean due to its affordability and durability.

Over time, Jamaicans have transformed bandana cloth into a symbol of national pride and cultural identity. Notably, folklorist Louise Bennett-Coverley, affectionately known as ‘Miss Lou,’ popularised the fabric by incorporating it into traditional performances, solidifying its place in Jamaican heritage. The bandana’s check design bears a resemblance to Scottish tartan, reflecting the historical connections between Scotland and Jamaica, including the migration of Scottish settlers and the influence of Scottish culture on the island, as well as on Chennai. Today, bandana is prominently featured in Jamaica’s national costume and is worn during cultural celebrations, symbolising resilience, and the enduring spirit of the Jamaican people. To learn more about this cloth, and other textiles worn by the enslaved, please see this excellent blogpost.

In our upcoming textile workshops, participants will have the opportunity to work with authentic Jamaican bandana cloth alongside locally sourced Scottish textiles. This hands-on experience aims to foster a deeper understanding of the intertwined histories and cultural narratives embodied in these fabrics, encouraging creative expression and reflection within the community.

The workshops will encourage participants to interpret what they have learned about Aberlour and Craigellachie’s connections to slavery and express their reflections through textile art, culminating in a banner for display in the church. In doing so, the community becomes active agents in shaping the narrative, bridging the gap between past injustices and present consciousness.

The image below comes from James Hakewill’s A Picturesque Tour of the Island of Jamaica, 1820-1821. Which you can view online here

Reflection, Responsibility, and Renewal

Projects like Legacies of Slavery do not offer easy answers. Instead, they provide frameworks for grappling with the moral complexities of history. They call on communities to recognise that the benefits of past injustices often still ripple through societies today—economically, socially, and culturally.

For Aberlour and Craigellachie, this means reflecting not only on the building of a church but on the lives irreparably harmed to make such philanthropy possible. It means accepting that history is rarely pure or simple. And it means committing to education, dialogue, and remembrance in ways that honour all parts of the story.

At the same time, the project highlights the possibility of renewal. By engaging children, parishioners, and the wider community in reflective and creative acts, Aberlour and Craigellachie are demonstrating that facing the past honestly can lead to stronger, more compassionate communities.

Looking Forward

The Legacies of Slavery project is part of a broader societal shift towards reckoning with uncomfortable histories. Yet it is also uniquely rooted in its local context, responding to the specific heritage, architecture, and people of Aberlour and Craigellachie.

In recognising the full story of figures like Alexander Grant and Margaret MacPherson Grant, the community is not tearing down its past but enriching it—making room for deeper understanding and a more inclusive memory. By integrating research, creative expression, and open conversation, Aberlour and Craigellachie are taking meaningful steps towards acknowledging their place in a global story of suffering, survival, and the ongoing quest for justice.

Through projects like this, small communities across Scotland are demonstrating that the legacies of slavery are not merely historical footnotes but living realities that deserve careful attention. In Aberlour and Craigellachie, threads of history, memory, and hope will be stitched together—one thoughtful conversation, and one piece of fabric at a time.